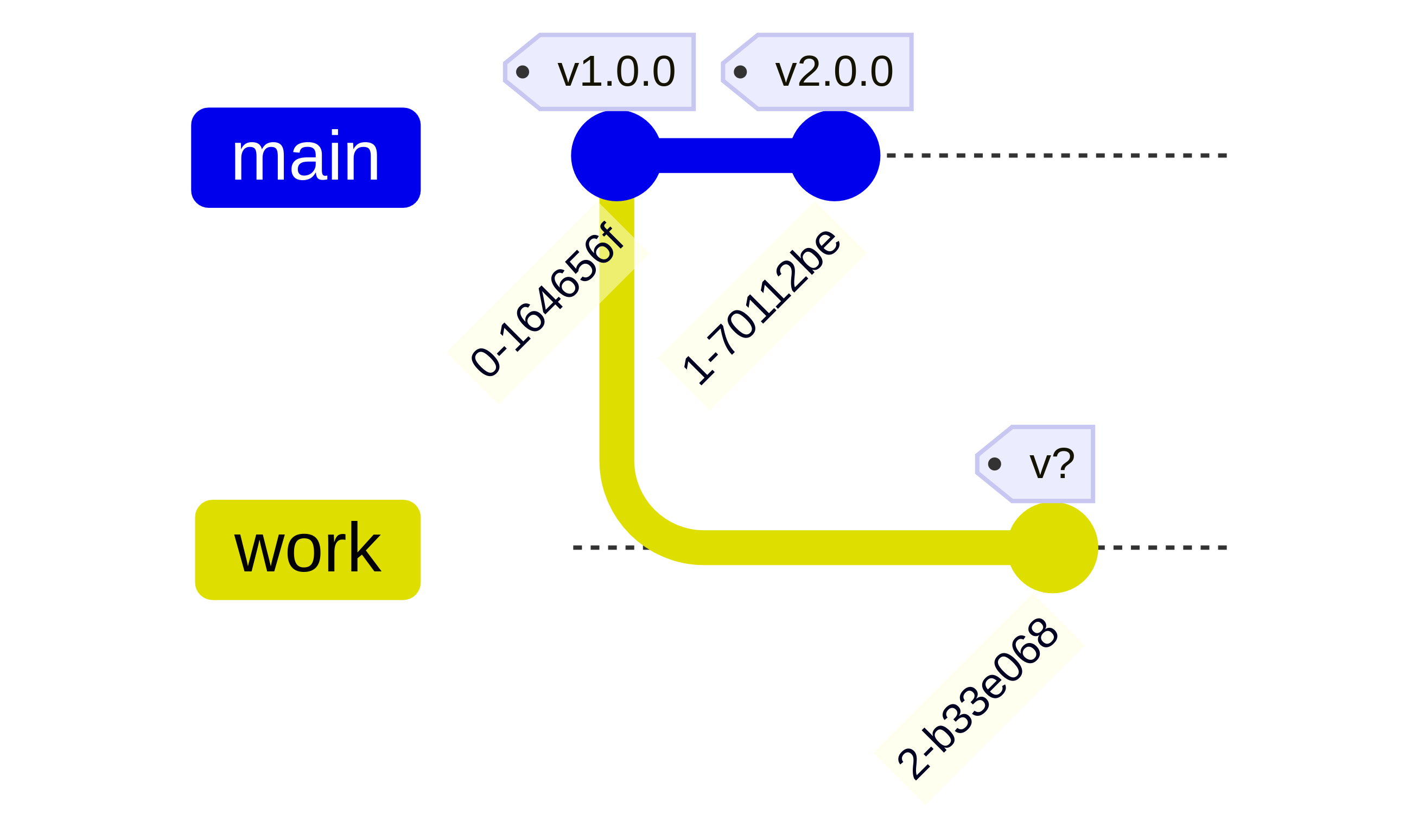

What to do if you need to do a breaking change to an old version? Here is an example, where we already created versions 1.0 and 2.0 and now want to change 1.0.

If we assume Semantic Versioning (SemVer),

it would have to be v3.0.0 for a breaking change.

However, it would be quite confusing to users if version 3.0 would not contain the change of version 2.0.

A more intuitive version would be v1.1.0,

but then we cannot claim to use SemVer which specifies:

Major version X (X.y.z | X > 0) MUST be incremented if any backward incompatible changes are introduced to the public API.

So, back to v3.0.0 to stay SemVer-compliant?

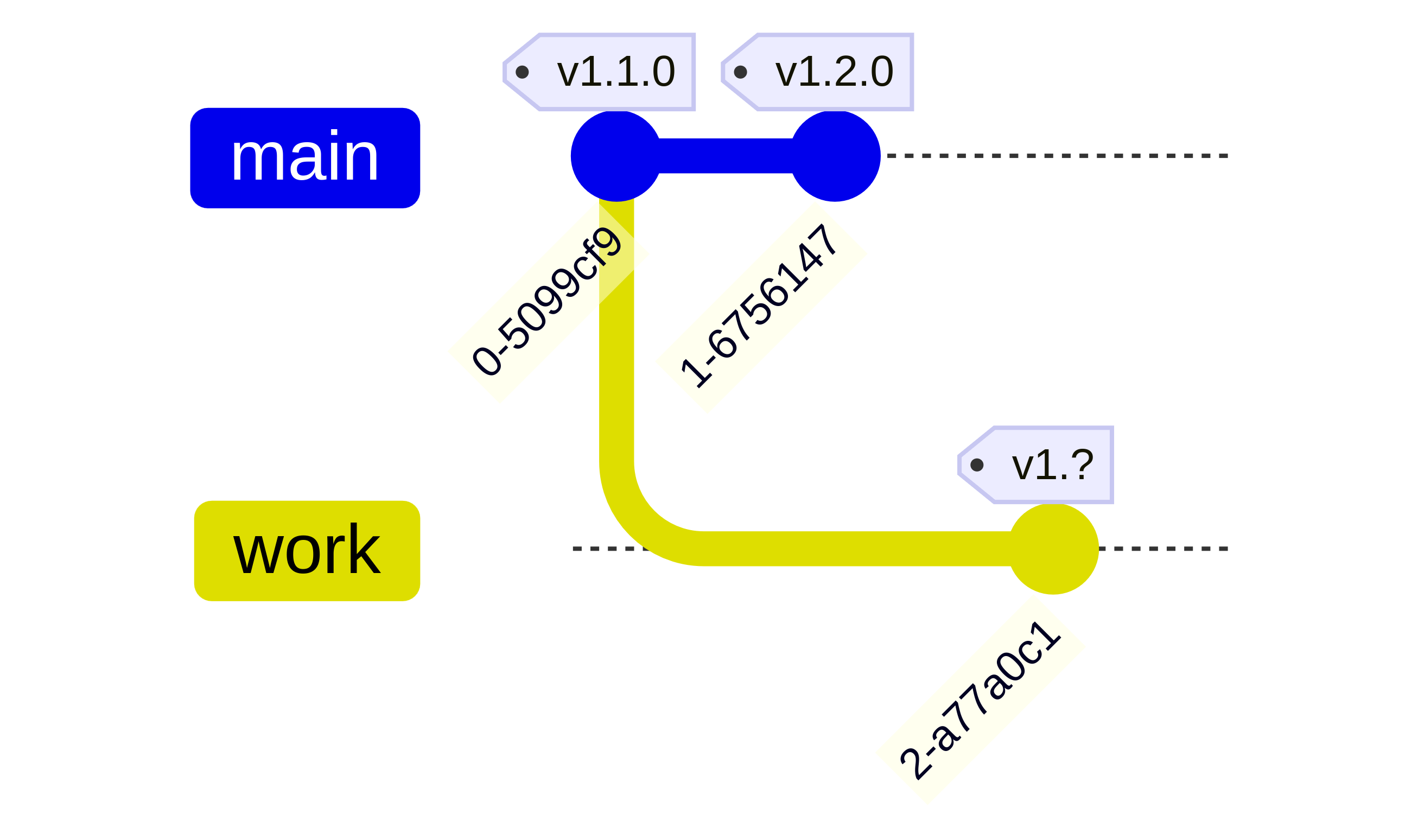

Imagine the corresponding scenario with minor changes adding functionality in a backward compatible way:

The SemVer-compliant solution seems to be v1.3.0.

However, a user updating from v1.2.0 to v1.3.0

would see the added functionality of v1.2.0 removed

which can easily be a breaking change.

However, SemVer requires you to update the MAJOR version for this.

SemVer cannot do trees.

The fundamental problem we observe is that SemVer is not designed for tree structures. No versioning scheme in broad use is. For example, calendar-based versioning is a linear sequence and hash-based versioning has no structure at all. The general idea is that versions can be totally ordered. That means you can always determine a "latest" version and when comparing two versions one is always higher than the other.

Version control, like git, obviously handle tree (or even DAG) structures. When users look at a list of version numbers, they don't see a tree structure though. Practically all versioning schemes look like a linear sequence.

Many people believe they use SemVer but are actually violating its semantics. Just because something uses MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH does not mean it is Semantic Versioning.

Many package managers extend or relax SemVer. For example, Conan extends the semver specification to any number of digits, and also allows to include lowercase letters in it. Bazel (more precisely bzlmod) uses a separate compatibility level, which is like a SemVer MAJOR version but without a definition for "compatible". Bazel also does not even try to select a "latest" version.

Your Options

Let's be pragmatic. What are the options?

If you try to stick with SemVer distributed on branches, you will probably see some mistakes eventually.

You can try to pick versions intuitively. Just don't claim that you use SemVer then, please. It is still easy to introduce weird behavior for users but at least you are not violating any self-inflicted rules.

If you document your intuitive approach, you invent your own versioning scheme. I once created SoloVer for fun.

In theory, this would allow for a scheme which supports arbitrary tree structures.

For example, "when you fork from a branch, append another .VERSION suffix"

but that could result in unintuitive versions with many dots, like v1.2.3.1.2.3.

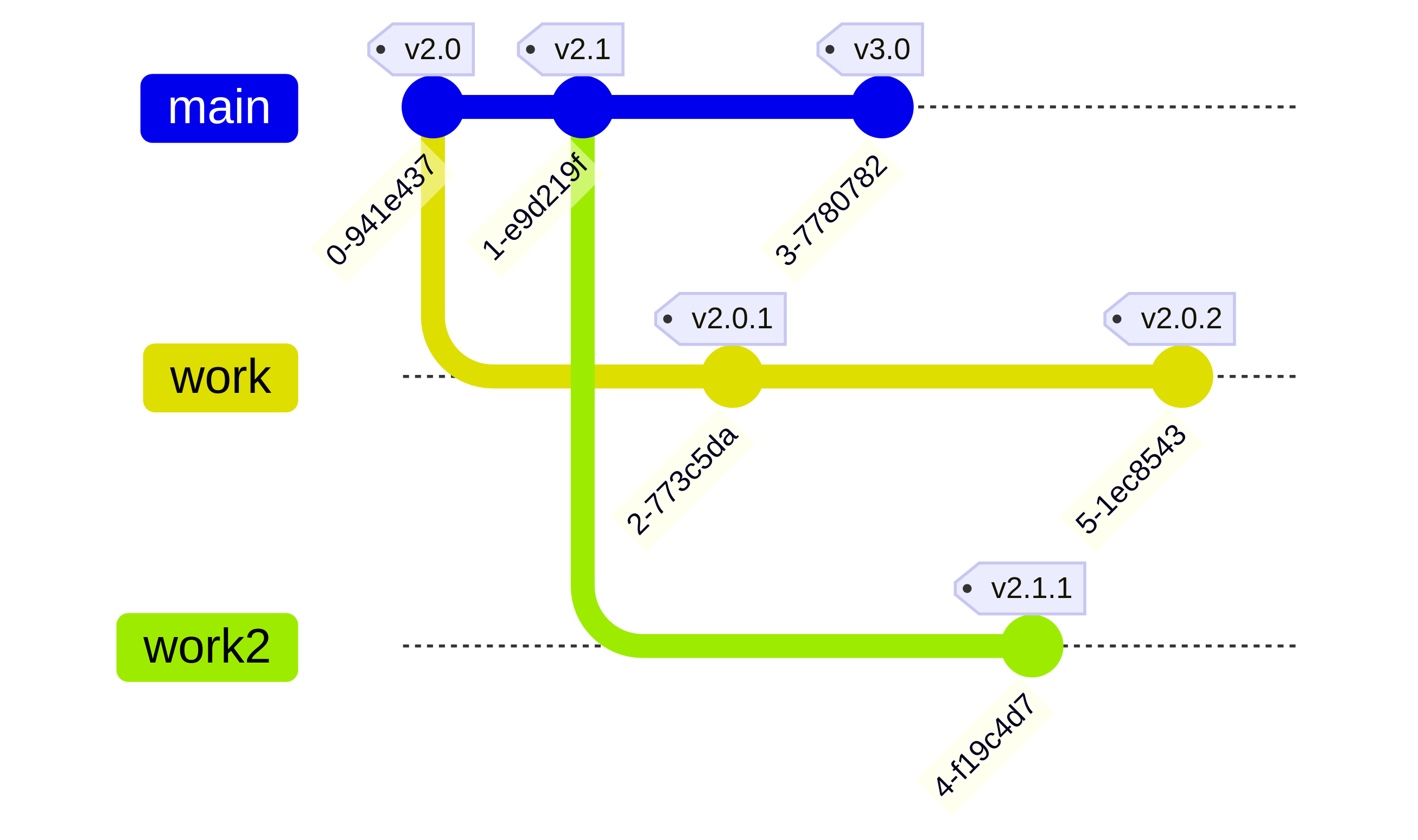

Actually, the MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH scheme allows for a restricted set of trees with at most three levels. It will not be compliant with SemVer though. For example, a pragmatic approach would be:

- The main branch only contains MAJOR.MINOR.0 versions compliant with SemVer.

- For each main branch version X.Y.0, you can fork off a release branch with X.Y.Z versions even if they are not backward compatible.

- You must not fork off from a release branch, so users may still have to accept unwanted changes sometimes.

You can fork the component to a different name. Quite a few projects provide "long term support" versions, for example. This provides a separate namespace for versions but you probably only want to do that for certain hand-selected versions. In the commercial world, this is what happens when you create a variant for a specific customer.

Finally, you could simply not do it. This means you sometimes have to tell your users that they must update to the latest version to get a bugfix. The simplest rule is to only version commits on your main branch. For independent Open Source projects, this is fine option (though security backports usually get an exception). If money is involved that might not be an option though.

As an aside: Whatever option you pick, you probably still want to cherry-pick stuff at least to your main branch. This implies that the same change (more or less) shows up in multiple release versions and this is another aspect which is not reflected in version numbers. Even version control systems like git do not model this well.

Whom to blame for the mess?

Imagine two friendly developers. Reese primarily integrates multiple components into an application. Finley works on one of those components.

Now, Reese is preparing a release of the application and a customer is waiting for it. Unfortunately, there is a bug in Finley's component, so a quick fix is needed. Meanwhile, they already released a new major version of the component which requires extensive integration testing. Reese demands that Finley patches the old version, so they can release the application as quickly as possible.

In my experience from similar situations, usually Finley will give in even if it means violating some versioning rules. I actually agree that getting working software to customers is generally more important than more or less arbitrary versioning rules. So I would not really blame either one of those friendly devs.

Instead I want to hint at a solution on a higher level. Push for continuous integration, by which I mean: develop stuff in tiny increments, value backward compatibility, and get rid of deprecations quickly. When Finley release in tiny increments, they can do it very often, like once a day. This implies the increments should always be backward compatible, otherwise Reese will be unable to integrate all the modules every day. To stay backward compatible, Finley will often have to use mechanisms like feature flags and deprecations, which incurs ongoing costs during development. If Reese does not get rid of the deprecated stuff, Finley's development speed will slow down more and more. However, if both of them keep up their end of the deal high speed is possible. (I don't claim it is easy)

With continuous integration, the above versioning issues become less severe. Until you achieve that though, you will have to pick one of the options above.